Internet Pitstops:

YouTube as a Place for Reimagining Social Time with Nostalgia

Srirachanikorn, Richy. 2025. "Internet Pitstops: YouTube as a Place for Reimagining Social Time with

Nostalgia." Time & Society:1-27.

This essay introduces the concept of internet pitstops to explain how and why YouTube has become a popular site for social timekeeping and expression. It reframes the cultural narrative that prolonged engagement with YouTube and specific short-form media is a symptom of ‘brain rot’. Instead, YouTube serves as an internet pitstop where individuals take shelter from the narrative that time has to be spent productively. It is this prolonged engagement with YouTube and its videos that social institutions come to label as unproductive, or media that causes ‘brain rot’. The essay draws on Henri Lefebvre’s notion of a ‘present without presence’ by arguing that social institutions use social time to impose pretexts over the context of time as a relational process between local actants. YouTube internet pitstops promote a reconstitution of time with presence: human commenters, the media content, and the in-built mechanisms reconstitute the present using social time. Crucially, nostalgia is integral to this contextual time that also reimagines the past, present, and future. Internet pitstops can be a useful theoretical tool for time scholars, nostalgia researchers, and sociologists interested in digital culture, time expression, and everyday life.

Keywords: internet pitstops, Lefebvre, nostalgia, social time, YouTube

Introduction

While social time generally refers to the frames of references that we draw from historical or cultural events to make sense of the past (Birth, 2017; Sorokin and Merton, 1937; Zerubavel, 2003), this paper is concerned with how people use social time inside a virtual space to reconstitute the present and the past, and crucially, to redefine the future. Consistently ranked as the second most visited website (Haan and Watts, 2024), YouTube offers people unparalleled access to social time, with around one billion videos being watched and millions of hours of videos uploaded per day (Adavelli, 2023; Cook, 2024). If YouTube lets us understand what happed in the past, albeit retroactively or vicariously, then who determines these narratives? Do they only come from ‘official’ videos published on YouTube channels run by governments, social institutions, or media companies? Or can users also contribute and challenge this time narrative with lived experiences and memories? This essay finds that YouTube allows for both: time narratives that social groups produce, which Eviatar Zerubavel (2003) calls time maps, and ones that are constructed by individuals, which Kevin Birth (2017) calls temporal landmarks. A closer look at these virtual sites – YouTube video pages – shows us that users do more than just learn about the past with time narratives; they congregate in these spaces to have past realities ‘re-activated and re-created in the present’ (Adam, 1995: 27). In other words, YouTube provides access to versions of social time whilst allowing users to (re)create their own.

These virtual spaces are what I have termed internet pitstops, evoking the real-world locations that drivers find rest, community, and a sense of time that exists far away from the inner-cities – or to be away from the ‘dominant temporal order’ (Sharma, 2022: 47) of social structures, time-based norms, and the temporal demands of one's working day (Zerubavel, 2003). Internet pitstops are a respite from the mandate of spending time ‘productively’. Adam (1995) reminds us that all reality ‘needs constantly to be re-activated and re-created in the present’ (27), but technological objects that ‘tell the time’ for us – clocks, calendars, and in this case YouTube videos – are de facto things that we look to for making sense of time, then and now. Similarly, Lefebvre (2004) finds that the media recreates all kinds of realities ‘by empty words, by mute images, by the present without presence’ (46–47). We understand the present and the past with objects that are pretextually imbued with a ‘dominant’ narrative. These objects embody what social institutions want us to think about time, how we should interact with it, and how we should spend it (Adam, 1995; Sharma, 2022; Zerubavel, 2003). Pretexts of time do not necessarily have to originate from social institutions. They are foremost normative, or ‘dominant’ ideas about time, that come to influence local contexts where reality is reconstituted, lived, and co-created by its actants. Although YouTube houses millions of videos produced by social institutions that ‘tell us the time’, historical documentaries, lectures, movies, the news, and government statements, there is no overarching narrative for how time should be understood. Each user accesses a single YouTube webpage at a time – as contexts – and encounter the pretext of ‘dominant’ social time narratives in certain videos uploaded by social institutions.

As such, internet pitstops are contexts where users can respond to pretexts by sharing their own lived experience of time in the comments, by replying to others, by liking comments or the video itself, and by using the time-stamp function on every video to specify what they are specifically responding to. These interactions are forms of social time expressions that, gradually with more views and engagements, uphold a new ‘dominant’ narrative inside the virtual context. This is what I will call social timekeeping, or the collective process – through digital interactions – of sustaining a social time narrative inside these contexts. For instance, users who visit a video compiling video game music from the 2000s may comment their nostalgia for childhood that enriches the music with lived time as a social time expression. Other users who agree with this expression may like the comment by the hundreds, turning it into a ‘top’ comment that other viewers to the page will see, and potentially, leave similar comments about childhood and like other ones. This gradual process of social timekeeping involves multiple actants – viewers, commenters, and the website's mechanics – that can reconstitute the virtual context, from a place of 2000s music appreciation, to a place for mourning childhood.

Notably, and as will be shown with the examples of three internet pitstops, users reconstituted the time narrative of the original video through social time expressions that revisits time nostalgically. YouTube contexts allows users to redefine time that exists outside of the ‘dominant temporal order’ (Sharma, 2022: 47) by using their own imaginations, speculations, and memories. Following Boym (2001), people are nostalgic for the past not ‘for the way it was but for the past the way it could have been’ (351), leading to a reconstitution of what time was like then and now. Therefore, nostalgia plays a crucial role in how users reconstitute ‘dominant’ social time narratives, but also as a reason for why people spend lots of time on YouTube itself. Ultimately, internet pitstops are a way that we can escape from, maintain, but also critique ‘dominant’ time narratives in everyday life. This is a chance to, following Sarah Sharma (2022), ‘reclaim time’ (47) without declaring a ‘new’ kind of time, but to keeping naming what controls our ideas of time and how ‘they can be both struggled against and joyfully averted’ (47).

Brain Rot or Respite?

There are two competing narratives for YouTube's role in our search for social time. YouTube's ‘Watching the Pandemic’ (YouTube Culture & Trends, 2020) report discussed the most popular types of videos during the COVID-19 pandemic from February to May 2020 ‘in search of a framework that might help explain them all collectively’ (YouTube Culture & Trends, 2020). In other words, why was YouTube a popular use of people's time during the pandemic? Drawing on anthropologist Susan Kresnicka's Human Needs Model, the report argued that video watching trends suggested users were searching for ways to fulfill their need for self-care, social connection, and identity. Yoga and Nature Sounds videos suggested that ‘people [were] in search of tools to cope’ (YouTube Culture & Trends, 2020) with the stresses of the pandemic by engaging in self-care. For social connection, the report noted that videos of people recording themselves performing day-to-day activities with the hashtag #WithMe ‘grew by 600%’ (YouTube Culture & Trends, 2020) towards May 2020, suggesting that users relied on YouTube for social connection deeper into the pandemic. Finally, the need to maintain one's identity was explained with a rise in cooking, gardening, and hair cutting videos, since ‘self-perception video[s] proved to be a unique way people could both express who they were and who they might become’ (YouTube Culture & Trends, 2020). Ultimately, the report suggests that YouTube was not just a place of social timekeeping – to maintain a positive narrative – but that it was where time expression is possible and beneficial, concluding that ‘we watch the same because we are the same’ (YouTube Culture & Trends, 2020). We express and maintain social time narratives because we need them. If we went as far as to create and maintain virtual spaces outside of YouTube to reconstitute time – Gathertown villages, Zoom Happy Hours, online video gaming, and virtual reality – then what happened when we returned to the ‘new normal’ after 2 years of home isolation? Eventually, YouTube embodied the critique for how time is spent ‘unproductively’ online, alongside platforms like TikTok and Instagram. Kathryn Campbell (2024) observes that anything labelled as ‘brain rot’ became…

Synonymous with the term ‘chronically online,’ [where] ‘brain rot’ is essentially used to describe useless, low value content online, usually Tiktok, that serves no purpose but to entrap the viewer into an endless cycle of doom scrolling… [so] it earned its name because some claim that watching such content makes one less intelligent… for hours on end until the only thing they know is the mindless motion of swiping and days worth of online jargon to recite like a pledge.

What exactly constitutes a ‘brain rot’ video is unclear. Tabboni (2001) writes that time is ‘not a biologically or psychologically determined phenomenon but a widespread social habitus which is accepted apparently spontaneously by nearly everyone’ (10). How else does a website praised for helping people find self-care, identity, and social connection ‘apparently’ and ‘spontaneously’ a place for ‘brain rot’? Part of the critique that comes from ‘brain rot’ content is that it prevents young people from communicating or expressing ideas without using internet jargon (Weekman, 2024). On YouTube, the internet video series Skibidi Toilet is often cited as a video that causes ‘brain rot’ due to its mindless entertainment value: a war between toilets with human heads against bodies with surveillance cameras as its head (CBC Kids News, 2024). The problem here is not one of miscommunication – that people who watch and adopt the vernacular of ‘brain rot’ videos have trouble expressing themselves – but more of an unwillingness of people who do not share this vernacular in wanting to understand those who do. For instance, one Tiktok creator noted that ‘they struggled to explain the Greek myth of Sisyphus without using a meme’ (Weekman, 2024) and that, consequently, this is a sign of brain rot.

The diagnosis is questionable when brain rot was first used in a 19th-century book that suggested human brains, like potatoes, could ‘rot’ (Yazgan, 2025), but nowhere did the author cite an inability to communicate fluently – normatively – as a symptom of ‘brain rot’. Instead, he suggested that the rotting occurs if people do not lead a ‘simple, minimal life… [if they do not appreciate] the beauty of nature… [or rid themselves of] invalid materialism’ (214). Here, the original label points to a pretext of time – a normative or a preferred narrative for one's use of time – that one should live slowly, beautifully, and non-materialistically. Colloquially, we draw from pretexts that tell us how spending time indoors, online, and alone are cues for these normative social time expressions: ‘go touch grass’, ‘live a bit more’, ‘go get a life’. Digital technologies may have decreased real-world activities like face-to-face social interaction, clocking ‘in-and-out’ of the office, dating and meeting people in the ‘traditional way’, or marketing door-to-door. But sociologically speaking, prolonged digital media use poses more of a threat to the status quo for how things should be done according to the chronometers of control (Sharma, 2022) rather than the social skills of all people. Young people and those who share the vernacular used in ‘brain rot’ videos can still understand each other, but they do so as implicated participants (Adam, 1995) who are taught that there is a time and place for these frames of references (Sorokin and Merton, 1937). This is to say, referencing online jargon in ‘real-life’ is not socially accepted. Hence, the idea that ‘brain rot’ content is ‘useless, low-value content online’ (Campbell, 2024) more closely reflects the inability for ‘the average1 person to comprehend’ (Weekman, 2024) and find meaning this social time expression.

Under neoliberal capitalism, where the expectation is that public time is always there (Tabboni, 2001; Zerubavel, 2003), we are never free from what Sarah Sharma (2022) calls the ‘dominant temporal order’ (47) that we must live around. Members of social groups may feel closer to each other with time narratives built for their communities (Birth, 2017), but individuals who identify as, or are dragged into a social group, are engulfed by its time definitions. One example is that coloured people are always late (Morris, 2023). If we apply this to a kind of ‘Young People's Time’, we can see that they are branded as a group where ‘the only thing they know is the mindless motion of swiping and days worth of online jargon to recite like a pledge’2 (Campbell, 2024). In an interview with young Canadians on watching and using language from ‘brain rot’ videos in ‘real-life’ settings, one person remarked that ‘it can be funny, but you almost feel guilty for laughing at it because it feels dumb. But if it wasn't fun, then it wouldn't be popular, right?’ (CBC Kids News, 2024).

Indeed, we can see the tension here between the influence of pretextual time and contextual time, where young individuals use these frames of references from online spaces to reconstitute reality (Adam, 1995) in local setting: at school, when hanging with their friends, or online. Contextual time is therefore the re-activation of the present involving local actants who interact, relate, and support one another. To point to Lefebvre, this is a present with presence. Conversely, we need not look further than the works of Sherry Turkle, the Australian government's ban on social media, or the common expressions to spend time outdoors and not alone, to see that pretexts of time influence how we live. Recent studies that systematically reviewed the ‘brain rot’ phenomenon built its case by linking prolonged digital media consumption with existing problems such as mental fog, anxiety, and poor emotional wellbeing (Yazgan, 2025; Yousef et al., 2025). Yet the authors admit that they ‘focuse[d] solely on the implications of low-quality content and its negative effects, particularly among adolescents and young adults’ (Yousef et al., 2025: 14), not outside of these determined categories. Of course, if we assume ‘brain rot’ media to be short-form entertainment content, albeit they are mindless and useless (Campbell, 2024), there is still the benefit that users share this content with each other (CBC Kids News, 2024), relate with the struggles of using internet jargon (Weekman, 2024), and even laugh at themselves for using ‘brain rot’ jargon in the ‘real world’ (Tiffany, 2025). For something that Yazgan (2025) labelled ‘as a problem of the century’ (218), they also write that older adults who feel isolated may benefit from this kind of media and the way in which they spend (prolonged) time with it.

We began with two competing time narratives that fought over YouTube's positive and negative role as a place for accessing and expressing social time. Yet, what we can see is that they are both pretexts of time that are socially negotiated (Tabboni, 2001) and implemented onto social groups and individuals (Sharma, 2022). Yet, these narratives lack detail for how individuals reconstitute time inside virtual contexts. Whether or not YouTube is a social time repository that leads to ‘brain rot’ or ‘brain respite’, people still engage with them to positively find, or brand negative labels on other's newfound self-care, identity, and community. We will now move to discuss why nostalgia is central to understand what goes on inside these virtual contexts and the kinds of social time expression and timekeeping that occur.

On Nostalgia and/as Social Time

Scholars have already pointed out that YouTube attracts high user engagement in the comment sections of videos covering controversial topics such as American politics (Heydari et al., 2019) and video gaming (Siersdorfer et al., 2010), making YouTube a viable source for social time expressions in response to pretextual time representing world events, culture, and politics (Breuer et al., 2023). Henri Lefebvre (2004) famously wrote that the media institution portrays ‘time [a]s–or appear[ing to be]–occupied. By empty words, by mute images, by the present without presence’ (46–47). Put another way, videos that perpetuate a social time narrative resembling time maps (Zerubavel, 2003) do not prioritise the accuracy of the events, nor the experience of living through that time; the goal is to maintain the ‘homogeneity and long-term stability’ (Birth, 2017: 29) of this narrative and the tie it has with the social institution itself. For instance, Donald Trump Jr.'s speech on YouTube proposed that the ‘America we all grew up with… feels like an old photograph’, that ‘somewhere along the way, we lost ourselves; but we can't live on nostalgia’ (CNBC Television, 2024). Interestingly, by evoking the perception that this America is forever gone – reinforced by the historicity of a photograph – he doubles down that Americans have also ‘lost [them]selves’. Logically, what is lost is due to age, the passing of time, and climate change affecting the sociocultural and geographical America they ‘grew up with’. What should be found is a renewed appreciation of the present despite these losses; to be grateful for what we have left. Instead, Trump Jr. insists that ‘we can't live on nostalgia’, signalling a push towards doing something in the present in the name of, and in spite of, the past – to vote and Make America Great Again. Here, the individual memory of the past is reduced to something that is blurry and static, as an ‘old photograph’. Essentially, one's relationship with time has to rely on the frames of reference (Sorokin and Merton, 1937) provided by political institutions instead of subjective markers.

Of course, not everybody agrees what the America in the past looked like; even people who grew up in the 1950s shared different accounts of what constituted their nostalgias for the decade (Wilson, 2014). Strategically, Trump Jr. never clarifies what this once Great America looks like to cause a sense of displacement, triggered by the statement that ‘somewhere along the way, we lost ourselves’. This ‘dominant’ but vague narrative of the past replaces the past that we remembered or lived through, leading to a displacement that Svetlana Boym (2001) posits can be ‘cured by a return home, preferably a collective one. Never mind if it's not your home; by the time you reach it, you will have already forgotten the difference’ (44). In this regard, the pretextual time of a Great America relies on individuals who takes on the nostalgic label that this past did occur – that we ‘lost’ it somehow – and who eventually develops a nostalgia to retrieve it; to Make it Great Again. Giving up the contextual time of a past America that one reconstituted with local actants: their family, friends, and memories, for Trump Jr.'s pretextual America is to adopt what Zerubavel (2003) calls time maps, which are cognitive tools that social groups and institutions use to portray a time in the past, albeit they are factually inaccurate. In other words, this dominant time narrative plays a larger role in re-activating the past (as it is understood in the present) over individuals’ lived experience and memorabilia. In a word, pretext trumps context.

Lefebvre (2004) thus noted that contemporary media no longer represents time that allows for presence, for things and people to speak and reconstitute time in its local context. Instead, time is an ontological space where the most dominant narratives of time prevails, as a ‘present without presence’ (47). As dominant narratives of time label things, people, and objects, these actants are no longer interacting at the local context but are tools that stand-in for pretexts of time. Sociologically, these pretexts of time are social time expressions that are ‘held intact by the structural demand that one must recalibrate’ (Sharma, 2022: 45). In other words, one has to live around the collective memory of the past that America was Great then and not now – despite their own lived experiences of a satisfactory present-day life. Trump Jr.'s America, albeit reimagined, is a pretext when he convinced his supporters to abandon their own individual frames of reference of experiencing time. In doing so, this reimagined past makes voters nostalgic for an ideal time they never lived through. Like the ‘brain rot’ narrative that pushed people to reject modern life (Yazgan, 2025), Trump Jr.'s Great America that his supporters never lived through requires that they vote in the present in order to bring back this past – to Make America Great Again. The call that we ‘can't live on nostalgia’ (CNBC Television, 2024) creates a nostalgia for a pretextual time, a past without presence, that people can only look to recreate in the present. Hence, after campaigning for 9 years on bringing back a Great America, Donald Trump proclaimed that this will ‘truly be the golden age of America, [and] that's what we have to have’ (Washington Post, 2024).

Moving away from time maps (Zerubavel, 2003) that institutions produce and towards a time that is negotiated between individuals with lived experience is to engage with what Kevin Birth (2017) calls temporal landmarks. In his interviews with Trinidadians, the concept of long time does not explain the mathematical distance of the present to the past but emerges as a reconstituting process of time between children, adults, and the older population. Evidently, adults and children who refer to long time always consulted the definitions of older adults who do not refer to long time but long ago, signalling the distance of having lived through the past (Birth, 2017: 76). A combination of time maps (Zerubavel, 2003) and temporal landmarks (Birth, 2017) appear as comments on YouTube videos of popular music from the 1950s to 2010s. Areni and Todres (2023) observe how pretextual time expressions such as ‘the good old days’ brought people together, but individual users enriched these sayings with their stories. One example wrote, ‘those were the days, great music and a great happy life!! I am 75 and I sure do miss the good old days’ (1460), whilst another said ‘that year… had some of the best songs… good voices and no auto-tune… good times back then’ (1460). With nostalgia, an emotional and subjective account led to a reconstituting of this social time in the present, as it was lived and felt.

Furthermore, research on nostalgic YouTube videos point to the context for how social time is reconstituted between commenters, the video content, and the playback mechanism. Notably, Sime (2023) refers to YouTube videos of feet injury and care during pilgrimage. Drawing on her field work, Sime notes a clash between older and younger generations of pilgrims in what constitutes an ‘authentic pilgrimage’ (39). Those in the older tradition felt nostalgic for when pilgrimage involved more suffering, less tourism, and more interactions with kind families’ donations as ‘practices on the edge of vanishing’ (39). Conversely, ‘21st century pilgrims, [seek out] older practices of care… [as they] become a marker of authenticity and… new forms of sociality’ (36) with their online audience. Despite a clash in experience, both generations benefit from the social time reference for what an ‘authentic pilgrimage’ looks like through YouTube videos. In particular, Sime (2023) argues that the ability to pause, replay, and share the still images of a pilgrim's injured feet allow audiences to immerse themselves in this captured nostalgia for the way they experienced it or hope to. Therefore, YouTube serves an actant that ‘transmit[s] and mediate[s] pilgrimage’ (52), embodying what Katharina Niemeyer (2016) described as digital nostalgia, or the longing for more than the media content and technology, but also the human relations that surround it. Via YouTube, older pilgrims yearn for the authentic social interactions they experienced, whilst newer pilgrims use this nostalgia to create ‘new forms of sociality’ (Sime, 2023: 36) online. As such, YouTube works in tandem with the individual to access social time and help reconstitute time for what it was and what it can become. Similar accounts were found with users who revisit skating videos and feel a nostalgia for their youth, the 1990s, and the content of the video – or the ‘look’ – as they are digitised versions of original VHS tape recordings (Thurnell-Read, 2022). Finally, Areni and Todres (2023) observed more nostalgic comments made in popular music videos of the 2010s than previous decades, reinforcing people's need to draw on social time (YouTube Culture & Trends, 2020), no matter how long ago or long time (Birth, 2017) they were. Nostalgia is therefore intertwined with social timekeeping and expression on YouTube.

Internet Pitstops

I want to reinterpret using YouTube as a repository of social time in quick succession – or by doom-scrolling – as a desire to absorb as many social time markers as possible. Memes, excerpts from world news, and commentaries on cultural trends are all things that we use as ‘social, rather than astronomical frames of reference’ (Sorokin and Merton, 1937: 619) to communicate with others. Platforms such as YouTube allows for its users to engage with a limitless supply of such content that is tailormade for them, as is the case with Tiktok's For You page, Instagram's Explore page, and YouTube's Recommendations. In this sense, the technology helps the user with an accumulation of social time that benefits both parties: the individual gets to share what they find culturally pertinent in future conversations, whilst the platform remains commissioned as user engagement skyrockets. Sime (2023) compares YouTube as a ‘cross between postcards and souvenirs’ (44), where the personalisation of social time videos via recommendations is the platform sending a public video to the user for private viewing like a postcard. On the other hand, users commenting and uploading their own time experiences produces a video or post that is like a souvenir, ‘evoking the memory of immediate experience and [that] they are a trace of that experience’ (44). In this regard, YouTube works in tandem with the user, the video content, and the playback mechanisms (e.g. sharing, still frames, timestamps) to maintain timekeeping whilst allowing for time expression.

Akin to real-world pitstops, YouTube provides its users with a temporary shelter from having to go back out onto the road of dominant social time narratives and structures (Sharma, 2022). In the local context of a YouTube video page, the human commenter, the video content, and the playback mechanisms interchange postcards and souvenirs (Sime, 2023: 44). Time maps that vaguely mention the past helps navigate users – like drivers – into a cognitive location, or map of this time. Despite its ambiguity, time maps (Zerubavel, 2003) encourage people to make something cultural personal (Sime, 2023), just as commenters of Areni and Todres (2023) felt compelled to elaborate their personal nostalgias of the ‘good old days’. In turn, individuals’ account of having lived that time embodies souvenirs (Sime, 2023) that people share and take as a reminder of a place (in time), reflecting the use of social time as a complementary device to existing time reckoning methods that are mostly quantitative (Sorokin and Merton, 1937). These individual accounts enrich social time by providing temporal landmarks (Birth, 2017), clarifying the specific qualities of the time in question.

The importance of internet pitstops is to expand on the nuance for how people interact with digital technologies, particularly of visual media, to cope with and create time. Contemporary research points to Reddit for its richness in anonymous long-form posts, its cost-effectiveness, and the ability to sample easily between related communities or ‘subreddits’ (Jamnik and Lane, 2017; Luong and Lomanowska, 2022). Studies that focus on YouTube as a site of time expression provide aggregate findings of comment types, keywords, and engagement statistics, but these do not explain the nuance for why individuals interact with YouTube in these ways (Thelwall, 2017). I argue that YouTube is an internet pitstop which helps people navigate through the messiness of real-world social time narratives on a day-to-day basis. At the individual level, Tabboni (2001) writes that work time never ‘demands total self-suppression’ (16) and that leisure time never ‘allows total release’ (16). Thus, ‘everyone has to find the ways [of continuing to live]… without going outside the field of tension created’ (17) by the two. At the macro level, social institutions discuss the past by proposing a restorative nostalgia (Boym, 2001) that deals with pretexts by turning things and people into collectible and categorisable objects of time (Lefebvre, 2004). Hence, the search for contextual time – and the place to reconstitute time locally – is necessary; nowhere is the individual and institutional clash between defining time clearer than the competing narratives that YouTube is a place for mindless and meaningful content (Campbell, 2024; YouTube Culture & Trends, 2020).

Internet pitstops reinterpret our interactions with digital platforms as a kind of relational time-making that involves a more-than-human ‘network of meanings’ (Adam, 1995: 5) between the commenter, the media content, and the in-built mechanisms. Together, they reconstitute the present with postcards and souvenirs (Sime, 2023), whilst encouraging a nostalgia that reimagines the past, present, and future. A working definition of internet pitstops is:

-

A place on the internet where people come to look for, and express, social time – drivers seek out real-world pitstops to rest and reorient themselves.

-

Involves a contextual reconstitution of time between human, non-human machines, and symbolic actants – drivers, cars, facilities that maintain a pitstop.

-

Remains conversational even after the original poster shared their social time and never returns to respond – graffiti in pitstop bathrooms walls are reconstituted by process of being drawn on, covered up by new writing, erased, and repeated.

Internet Pitstops 1: Postcards and Souvenirs of the Past

Published in 2010 by the media channel, Discovery UK, the YouTube video ‘Reagan Assassination Attempt’ provides a 2-min 11 s account of how the late U.S. President survived his shooting on March 30, 1981. This cultural frame of reference acts as a time map (Zerubavel, 2003) recounting the event where Ronald Reagan and three others were shot. But rather than provide interviews, voice excerpts, or clippings of the time that the injured and present experienced, the video discusses the previous limitations of the Secret Service's security protocol, its present (at the time) detail, and the future improvements made after the attack. Discovery UK's time map of Reagan's shooting neglects the qualitative detail of this social time as it is lived and felt, despite Sorokin and Merton (1937) insisting that social time is ‘qualitative and not purely quantitative’ (624). What contemporary viewers are given is a 2-min video with more frames of reference about the Secret Service than of Reagan himself, who is the subject of the video's title!3 As such, the pretextual time narrative here is that Reagan's shooting, whilst shocking, led to a necessary improvement in security of the U.S. government. This time narrative is less concerned with an accurate portrayal of events as it happened, and more concerned with maintaining ‘homogeneity and long-term stability’ (Birth, 2017: 29) of the social structures tied to this narrative (e.g. the Secret Service, the U.S. government).

In Reagan's video, YouTube comments reveal temporal landmarks (Birth, 2017) through anecdotes that ‘[Reagan] actually told the surgeons after his surgery: ‘I hope you are all Republicans!’4 and that ‘[he] held a speech a few months after this event, where a balloon popped but it sounded somewhat like a gunshot. He did not even flinch and just threw the words ‘missed me…’.5 These elaborations create a forum in which time portrayed as history can be discussed rather than disputed (Lefebvre, 2004). Similarly, temporal landmarks (Birth, 2017) allow for individuals to engage with the social time portrayed by bringing it into the present. Two commenters wrote, ‘We all know why we are here’6 and ‘Who's here because trumps failed assassination attempt?’.7 Each of these were published in August 2024 and garnered around 2500 likes and 50 comments by the time of writing,8 suggesting that more people are engaging in social time as a referential tool between the recent and the long gone past. In another video published by media institution Inside Edition (2019), ‘Inside Ronald Reagan's Funeral’, users shared their personal nostalgias for how ‘[they] always miss President Reagan… forever’.9 Conversely, others shared how this time personally impacted them even if the author ‘wasn't alive during the time [Reagan] was president but I can tell he was a great guy’,10 or that, ‘My Dad was truly devasted… he told me he watched his funeral… and I believe that he got a little emotional while watching it’.11 Here, we can see how time maps (Zerubavel, 2003) may instill a sense of nostalgia that social institutions direct – e.g. when things were Great Again – but temporal landmarks (Birth, 2017) encourage a contextual nostalgic reading of time that is lived, that is relational, in which social institutions cannot always anticipate or control.

YouTube serves as a remote place – as an internet pitstop – away from ‘dominant’ social time narratives where school history books, televised documentaries, and official government statements memorialise the President in a preferred social time narrative. To be clear, these narratives are ‘dominant’ not only because they are told by social institutions, as time maps (Zerubavel, 2003), but also because people include these narratives into their routine (Zerubavel, 2003), habitus (Tabboni, 2001), and the way they structure their everyday lives (Sharma, 2022). Dominant time narratives are normative. Particularly if historical narrative leads to nostalgia, people are likely to retell an inaccurate version of the past as history (Wilson, 2014). Nostalgia, like social time, ‘does not flow at one even rate, but goes at a thousand different paces… which bear almost no relation to… traditional history’ (Braudel, 1980, as cited in Birth, 2017: 72). Indeed, there is no single narrative that history books, documentaries, and government statements provide, but their influence into YouTube videos plays a large role in the social timekeeping for what appears as historical time. Boym (2001) already warns us that nostalgic pasts which appear historical are more social than they are otherwise: nostalgia is never literal but lateral. That is to say, we should consult social time narratives as tools to make sense of the present – to debate, to reference, to uphold – reality in a context as it is being locally and collaboratively reconstituted (Adam, 1995). YouTube offers individuals with more agency in revaluating what constitutes this historical or ‘dominant’ social time precisely because of their nostalgia. Commentors who provide anecdotes or cherished stories about the late President may not challenge the ‘dominant’ narrative by critiquing it, but the mere fact that – on a YouTube page – the social institution's role has reduced to a single actant (e.g. the video) means that the battle ground for reconstituting time has shifted in favour of individuals. In other words, the composition of who and what constitutes the present, now with more presence (Lefebvre, 2004) of those who may have lived through it, ‘challenges’ how we may think about the dissemination of ‘dominant’ or ‘historical’ time: press secretaries convey an administration's stance of an event as historical, inconsequential, or overly significant, then the media tells its viewers a particular framing of that argument, before individuals – who lived through it – have a fighting chance to contend, or even be heard. On YouTube, social institutions or authoritative figures have to contend with the collective sentiment of the comment section which, through social timekeeping, can quickly override the narrative of the video. For instance, on one video page, users engage in a social timekeeping that nostalgically celebrates Reagan's legacy, but only a click away, users in a different video who lived through Reagan's two terms are nostalgically mourning the past that they felt Reagan had made worse for them. How social time is reconstituted on YouTube thus ‘challenges’ the way we think about the composition of presence within the present.

Here, individuals can extend the social time to themselves nostalgically, as internet pitstops are where people search for and use social time. To translate with Sime (2023), the time map (Zerubavel, 2003) of these videos acts as a ‘postcard’ that makes a cultural event personal, whilst comments are temporal landmarks (Birth, 2017) which resemble ‘souvenirs’ which individuals share and keep. Together, they reconstitute the past with emotional insight into the time of the 1980s and 2024 for when two shootings took place. What could have been a directed account of time helmed by an institution became a relational engagement of individuals with, and who elaborates on, social time. I will now point to a second internet pitstop featuring non-human actants, the video content and the timestamp mechanism.

Internet Pitstops 2: 'I Really Miss the Old Future',

or The Future is in the Past

One genre of YouTube videos which take media products of the past and bring them to the present are known as Vaporwave. These videos are a collation of media texts, products, music, and events from the ‘1980s to the mid-1990s, encompassing the childhoods of Generation X and early Millennials’ (Cole, 2020: 300). But rather than present these things as being lost to a time in the past, thereby reinforcing its status as an object of the 80s, it remixes old nostalgic things to form a new nostalgic experience. An important distinction to make is that Vaporwave is a practice that individuals partake in, whereby a ‘hypothetical production… [could be combining] Carly Simon's Coming Around Again with a 1982 Philips VLP-700 laserdisc player ad’ (2020: 301). To clarify, this video and music pairing never existed in the 1980s, making it novel. Yet the mixture of old things to produce new unseen pasts may prompt individuals to think about the past for how ‘it could have been’ (Boym, 2001: 351). As such, individuals move away from feeling restorative nostalgia (Boym, 2001) produced by social institutions, and towards a reconstructed nostalgia (Ballam-Cross, 2021) that asks a critical question: What really defines the nostalgia I feel for the 1980s? Behind this social time, what objects are told to me to embody that era? If I indeed lived through that time, what things, products, or futures were presented and promised by media institutions which never came to fruition in the present day? This last point is the most crucial, given Vaporwave borrows the term ‘vaporware’ from the 1980s to describe software and technologies that were promised by companies but never released (Dovydaitis, 2021). When applied to time – particularly the present and the future – one can start to engage with the pretexts they use as social time markers. Together, Cole (2020) and Dovydaitis (2021) insist that the goal is not to define what Vaporwave looks like, but to understand that ‘Vaporwave is about capitalism, [as] it sonifies and visualizes it’ (114). In being able to re-encounter objects of time, individuals can reinterpret them as things and people (Lefebvre, 2004) that reconstitute the present moment of feeling nostalgic.

Similarly, a lesser-studied internet aesthetic that does this is Frutiger Aero, which Sofi Lee coined as the dominant design choice that companies used on technologies, software, media objects, and products from the early 2000s to 2014 (Holliday, 2023). Where Vaporwave depicts objects of the 1980s and 1990s, the most illustrative forms of Frutiger Aero are the ‘look’ of Windows XP, Windows 7, and early iPhone digital interfaces. Its aesthetics are defined by its hyperrealist representation of things and people, or ‘skeuomorphism, [with] glossy textures, vibrant colour palettes… and nature-inspired elements such as cloudy skies, tropical fish, water, and bubbles’ (Frutiger Aero, n.d.). Ostensibly, this harmonious and clean future provides a positive look on the future, but ultimately its tie in with media, commodities, and technological products that are now outdated reminds us of the promised future which we lost. If we link this with Mark Fisher's (2014) idea of hauntology, which is the feeling that the past continues to linger in the present because we are unable to reconstitute the past, present, and future without the pretexts of institutions dictating this, then one's frustration for losing this future may stem from the physical and digital presence of these computers that are still being used today. Fisher (2014) thus reminds us that the challenge we face is not satiating our nostalgia – the desire to return to the past – but it is to get out of a culture haunted by the past that happened and the past that could have happened. For instance, Vaporwave videos present viewers with a romanticised version of the 1980s shaped by messages, edits, and commercials of cultural institutions then – as pretexts – so users in the present may turn to commodities sold as ‘Vaporwave’ products in conjunction with this restorative nostalgia of the ‘80s Vaporwave look’ (Boym, 2001). We know that consumers satiate their nostalgia with objects that are mass produced rather than unique, or with an imagined past that is collective, rather than personal (Cross, 2015; Jacobsen, 2021). As such, it is probable that Frutiger Aero videos – with its compilation of products and music from the 2000s – will push users to buy things labelled ‘Frutiger Aero’ that social institutions profit from.

Even so, I want to argue that this does not take away from the power of internet pitstops. Users who go out to purchase things that resemble the Frutiger Aero look may not do so because they believe in the restorative nostalgia (Boym, 2001) that the 2000s–2014 looked like that. In fact, some consumers purchase things that resemble the past to own something that gives them ‘comfort and a sense… to slow down life’ (Jacobsen, 2021: 14). Brown et al. (2024) thus write that these ‘these seemingly mundane images of outdates consumer-capitalist [products]… become reminders of how the future was once collectively imagined’ (1721). It is important to distinguish that Vaporwave videos create a nostalgia now that demands a return to back, whether this is the past that was lived or reconstructed, but Frutiger Aero videos remind its users of the nostalgia they had since the past of a future that they had hoped for but never came to be (Holliday, 2023). In other words, the nostalgia that viewers have for Frutiger Aero is not really the 2000s–2014 because it was not glossy, saturated, eco-friendly, or naturally harmonious. Frutiger Aero products embodied the future that would have looked like this. As such, the nostalgia for Frutiger Aero is not backwards looking; it reminds us that we are still looking forward to a future that is still buried as a failed promise in past. As such, people may purchase ‘Frutiger Aero’ items or refer to them fondly to redeem the souvenirs and postcards (Sime, 2023) of a time they never got to live through. This common disappointment for an anticipated future of glossy, eco-friendly, naturally harmonious, and hopeful world (Holliday, 2023) ends up bonding people together. Ironically, it is the pretext that social institutions in the past tied these objects with – a hopeful and glossy future – that their consumers (who have now grown up) are using to critique them.

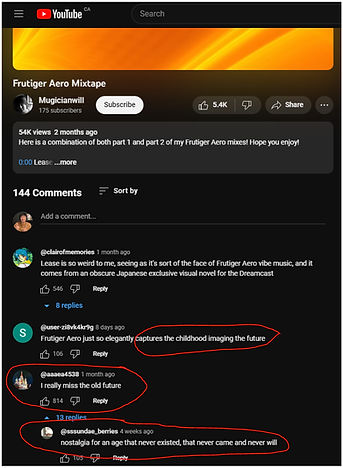

The video ‘Frutiger Aero Music Playlist’ (skeuoss, 2024) serves as an internet pitstop where these frustrations and realisations occur. At the time of writing, a comment that said, ‘The future we wanted, but didn't deserve’12 attracted 352 likes and 7 replies, and one that wrote, ‘From children [sic] this was the world we were promised, no wonder so many are disillusioned. It's such a bitter sweet [sic] art style’13 garnered 1 thousand likes and 7 replies. One user14 revealed that:

‘What I love about this aesthetic is how much positivity it displays. The bright colors and the cleanliness of it all, it envokes [sic] a sense of hope for the future. A future where we achieved world peace, where the planet was cleaner than ever, where everyone and everything was happy. A future that I don't think we’ll ever be able to achieve’

Although the disappointment and frustration are there, the nostalgia for the past that ‘could have been’ (Boym, 2001:351) is better expressed with the use of timestamps. Timestamps are an in-built YouTube function where users write two sets of numbers corresponding to a moment in a video, turning blue once the comment is published, and readers of said comment who click on the timestamp are redirected to the exact moment in the video which these numbers refer to. Its use is important to create what YouTube calls ‘Chapters’, or a period of a video that is marked between two timestamps, though importantly, they help users pinpoint specific moments where they felt nostalgic. For instance, a commenter specified ‘3:00:52 [as] THIS MUSIC IS MY CHILDHOOD OMG THIS IS FROM NINTENDO DS PHOTO ALBUM’,15 whilst another replied, ‘same :)’.16 Likewise, the YouTuber skeuoss included timestamps in the video description so that users can identify the song that is played. Where Niemeyer (2016) identifies digital nostalgia as a longing that goes beyond the media artifact, but also the human relations which surrounded it, we can see how the timestamp functions to make this nostalgia for the past a shared context in the present. Other users who come across this comment can experience the nostalgic moment as closely as the original commenter did when they are redirected to the exact song in the 7-h video that prompted the user's temporal landmark (Birth, 2017). A collection of social time expressions: the timestamp mechanism, the human commenters, and the video content worked in tandem to contextually express a nostalgia for a present with presence. Together, they produce a social timekeeping that turned a video compilation of media artifacts from the 2000s–2014 that may at first seem like a perpetuating of restorative nostalgia (Boym, 2001), to a nostalgia that rejects and demands this promised reconstruction from back then to actualise now. Remarkably, another comment wrote down 6 timestamps, elaborating with a sentence below that said, ‘These sounds really give me goosebumps’.17 Where YouTube is commonly thought of as a platform of individual social time records, this comment – and the video – becomes a mini timekeeping repository where readers can experience 6 videos worth of nostalgia within a single timestamp-filled comment, within one context. In these cases, the timestamp works to help individuals who come searching for social time to do so easily through Chapters and time-stamped comments, whilst individuals who want to express their nostalgia can do so specifically. As well as the timestamps, users who remember growing up with these products, to echo Cross’ (2015) consumed nostalgia, can find many frames of reference inside Frutiger Aero videos to discuss, relate, and connect with others galvanised by this lost future (Fisher, 2014). This visual and sonic nostalgia encourages users to re-activate the past-promised future in the way they wished for it to be, in the way it ‘could have been’ (Boym, 2001: 351). Frutiger Aero thus proposes a nostalgia that demands action over reaction.

If internet pitstops are a curatorial use and reimagination of social time, an interesting question for future research should be what political and social actions do these digital spaces motivate? Discussing climate change movements, Friberg (2022) identifies how the future is sometimes framed as postapocalyptic and as dependent of present actions despite being a larger and unpredictable entity than anyone can control. By tying the present with the future through an existential calling, a temporary utopia emerges as ‘images of what society could look like one day and therefore offer a sense of being part of a collective endeavour’ (61). Frutiger Aero may not have formed as a political movement, but a collective sentiment of yearning for the past, albeit as a future, that lingers in the present (Fisher, 2014) may lead to insights about ‘the rhythms, pulsations, and beats of the societies in which they are found’ (Sorokin and Merton, 1937: 623). If Brown et al. (2024) write that visually, Frutiger Aero reminds of the future that could still be, and internet pitstops reveal a generative effort to reimagine this with human commenters, YouTubers, the video content, and the timestamp, then there is potential where a new kind of anti-time space is realised. Such an effort speaks to Boym's (2001) lesser explored ‘creative nostalgia [which] reveals the fantasies of the age, and it is in those fantasies and potentialities that the future is born’ (351). Frutiger Aero contexts are also constantly at risk of disappearing as they utilise music that companies own, meaning that these videos get taken down on a regular basis. Scholars who are interested in how disenfranchised individuals use digital spaces to connect with each other should consider Frutiger Aero videos as internet pitstops that hold these potential insights. As one example, this is an annotated screenshot of an internet pitstop that I took in November 2023 before the conception of the ideas behind this essay. Today, that video (Figure 1) is no longer available along with the souvenirs and postcards (Sime, 2023) of a nostalgia for the ‘old future’ that never came, and now, no longer exists.

Internet Pitstops 3: Writing for the Road, or a Legacy of Presents with Presence

Originally a YouTube channel uploading videogame music, taia777 attracted millions of views to the video, とげとげタルめいろスーパードンキーコング2", which translates to Thorny Tarmeiro ‘Super Donkey Kong 2’, a reference to the 1995 game published by Nintendo. By various accounts, the video was removed in 2020 (Oxijinn, 2023), and the channel was taken down in 2022 (Wikitubia, 2024). As a media company, Nintendo is controversial for its history of taking down YouTube videos that include content from their games and music, even if they are made by fans and supporters (Moreno, 2022). The reuploaded video by Oxijinn (2023) currently sits at 54 million views and 213,138 comments at the time of writing.

Per the first definition of internet pitstops, the video content includes the ‘Donkey Kong’ videogame music as a social time marker of the 1990s. But different to Frutiger Aero commenters who embraced past media objects and music that they grew up with, commenters of this video focused on the recent past and the present. Some commentors celebrated incoming or recent personal milestones, such as ‘Checkpoint: I’m gunna be a dad’,18 ‘Checkpoint: Just performed my first gig as a pianist; it went smoothly…’,19 and ‘Checkpoint: Finally quit a job I hated and started doing something I love. Game saved’.20 Conversely, others expressed dread for the present and future such as, ‘Checkpoint: scared, going though [sic] sone [sic] things.. i just feel like i don't exist. and at one point i will go missing and 10 months later come back, where no one remembers me’.21 Remarkably, each of these comments received support from other users through ‘likes’, encouragement, or expressions of similar experiences. Incidentally, the word ‘Checkpoint’ is also used by video gamers to describe an area in a game where players can save their progress and, upon death, are guaranteed to be transported back to the checkpoint without having to start all over again. These postcards and souvenirs (Sime, 2023) therefore act as social time markers that are ‘dialogic, socially oriented process[es] of crafting one's identity’ (Birth, 2017: 74) but also the ‘beautiful community of commenters’ (Oxijinn, 2023). This internet pitstop therefore promises access to social time which does not to lead to anything or anywhere that social institutions control. By using a ‘checkpoint’, one is guaranteed to always return to this contextual space of time-making without the disappointment and allure of pretextual social time.

Nonetheless, some users do return to their original comments and edit the post with an ‘update’ for a second Checkpoint. For instance, one user initially left a ‘Checkpoint: i’m finally getting better after four years of depression, im 2 months clean from SH and my life is getting back together’, before leaving an ‘UPDATE [where] 5 months later, im 4 months clean, got diagnosed with ocd and persistent depressive disorder, on meds for both of these. my life is so so SO much better…’.22 Another commenter left a ‘Checkpoint: I just slept in my new home for the first time after being homeless for 4 months, im 19, working full time now, and feel better then ever, im safe.’, before an ‘Update: Damn its been 2 months already huh?… im in therapy now and living happily…’.23 It is noteworthy that these two self-updated checkpoints also thanked other commenters for their support. If we are reminded of Sime (2023) who argued that YouTube videos are like gifted postcards, where something public is made personal, we can see this exact dynamic where a public comment section personally engages with the commenter's lived experience.

Drawing on the second definition of internet pitstops where YouTube mechanisms are actants that reconstitute the present, the ability to leave, respond to, and edit one's comment allows for a reconstitution of the present that is contextual. Beyond the local YouTube page, we can also see a resistance against Nintendo and its control of social time as media institutions since ‘a truly beautiful place of the internet, [was] once desecrated by stingy copyright owners, who don't allow for joy if they don't profit off of it’ (Oxijinn, 2023). Like the deleted Frutiger Aero video in the previous section, whenever Nintendo takes down videos of their intellectual property that individuals upload, they also take away the virtual context for people to exchange postcards and souvenirs (Sime, 2023) to slow down the present (Jacobsen, 2021) or to revaluate the restorative nostalgia of the past as told by commodities and ‘dominant’ time narratives (Brown et al., 2024). Taking away these virtual contexts is akin to demolishing the post offices that individuals use to send others their postcards (Sime, 2023) of a past for the way it could have been – to divert from the ‘dominant’ time narrative that dictates the present without presence (Lefebvre, 2004) – or to retrieve souvenirs (Sime, 2023) that reminds them of the past for the way it was – to slow down time (Jacobsen, 2021). Without internet pitstops, individuals who want to reconstitute the past and present have only pretexts of time to look to; ones that Nintendo uploads onto their own channel and other ‘official’ platforms, sells as commodities that embody a particular version of the past, and monitors with copyright takedowns. As such, other internet pitstops are formed in retaliation, all with their own presents with presence (Lefebvre, 2004): multiple YouTube channels reuploading the original video, a wiki page documenting the history of the channel, a website preserving the original videos and its comments as screenshots, and online communities formed on Reddit as well as social media platform Discord for commenters to continuing chatting and supporting with one another. Continuously reuploading media that institutions like Nintendo try to control – to keep it in the past, or to allow only uploads from its own channel – is a form of resistance.

What is remarkable with the video is that it does not include a movie that is produced by an institution, like Reagan's funeral and shooting, nor does it include a rolling projection of objects that promise a future that is in the past, like Frutiger Aero. Instead, the video consists of a looped image of pixelated green thorns covering the backdrop of a blue sky with clouds (Figure 1). The lack of a guiding social time object means that this internet pitstop is constituted of social time that individuals co-create for one another. Individuals who leave and update their checkpoints invertedly form a frame of reference in which they look back for progress, whilst others who never return to edit their checkpoints still serve as motivation for others who are searching for similar experiences (Figure 2).

Figure 1. 'I really miss the old future'. Screenshot by Author.

Figure 2. Green pixelated thorns and blue backdrop. Screenshot by Author.

This active effort across commenters, checkpoint creators, platforms, and its local non-human actants illustrate the third definition of internet pitstops. Akin to walls of real-world pitstops where graffiti and messages are talking to one another without the writer physically there, this internet pitstop operates in the same way where previous comments, or even a series of videos, continue to reconstitute the present even without the presence of the original. With this, users can take respite in this niche corner of the internet – like remote pitstops on a long rural road – whilst returning to their comment or reading others to feel a sense of progress. Put another way, they can use social time to fulfill a time narrative that is based on their nostalgia of the past or the future, undirected by social institutions. I now conclude with a comment that perfectly captures the description and significance of internet pitstops:

Life is so strange.. im 27 years old, and never encounted [sic] the original internet checkpoint. And seemingly out of nowhere, i get recommended this video in the same way many others have. The japanese text, the unassuming backround.. [sic] I cannot explain the instantaneous flood of emotion that came over me. It is one of the most human experiences ive ever had. Reading all of these stories, struggles, and glimmers of hope gives me the strength to continue. While I may not have been there to see the original, this hit me just as hard. The battle continues, and I must move forward. Thank you kind strangers, you have given me the hope and courage I needed this day. With love, I wish you all the best in life. Checkpoint reached: 6/6/2023.24

Conclusion

In this essay, I have shown the importance of digital platforms such as YouTube for providing individuals with access to social time that can be beneficial to their positionality and communication with others. Yet, the role of YouTube as a provider of social time is, at best, seen as a need for human connection (YouTube Culture & Trends, 2020), and at worst, a cognitively degrading activity (Campbell, 2024). To get a better understanding for how and why millions of people flock to YouTube daily, I looked at three virtual contexts where time is potentially reconstituted with more presence (Lefebvre, 2004). That is to say, the role of social institutions in determining the normative or ‘dominant’ time narrative has to contend with viewers, commentors, and the like/dislike ratio that can overturn it. With each of these social time expressions, YouTube users can enforce a kind of social timekeeping that either supports – and enriches – the time narrative produced by the video or divert from it – even going as far as to critique it. As such, YouTube internet pitstops can challenge how we think about the reconstitution of social time.

One critique however is that internet pitstops do not actually liberate people from the control of pretextual social time narratives because they simply recycle what social institutions produce. On Reagan's shooting and funeral, viewers experience this sequence of events through an edited, narrated, and controlled format that gives it the status of a ‘historical’ video. Similarly, the second example of Vaporwave videos involve curators – more individuals and less so social institutions – who look to images of products released in the 2000s. Users may at first critique the future that never came through a nostalgic disappointment, but many others may seek out ‘Frutiger Aero’ products that are made to satisfy this nostalgia. As Boym (2001) reminds us, in contemporary life, nostalgia always arises from interaction between subjects and objects. One reason for this is that under postmodernity, the distinction for what belongs to the past is blurred and where ‘home’ is no longer clear (Wilson, 1999). Thus, it is easy to give into nostalgic readymades (Boym, 2001) instead of committing more money and time to pursuing the original (Cross, 2015). Indeed, even the most critical internet pitstop of Taia777's video borrows Nintendo's music to situate its viewers to reconstitute this reality of checkpoints.

I would like to contend that this is precisely the power of internet pitstops; the fact that they recycle social time expressions that institutions produce means that strangers can quickly relate with one another with souvenirs and postcards (Sime, 2023) that are culturally recognised. Yet, the composition of these virtual contexts – as sites of brain respites rather than brain rot – demands that individuals work in tandem with social time expressions: comments, view counts, time-stamps, the like/dislike ratio, and other videos on this topic, to reconstitute the narrative for how the past is understood (per the video) and how the present is affected by it (per the context). From this interaction, users perform a social timekeeping that already challenges how time is constituted with a more democratic, or more local-based, composition of actants (Adam, 1995; Mead, 1934). Moreover, nostalgia is a powerful tool that keeps people committed to curating internet pitstops. In the Frutiger Aero video, we learnt that users continuously refer to objects of the past not because they are infatuated with the 2000s–2014 that looked glossy and saturated, but that they are lingering reminders (Brown et al., 2024) of the future then, or the present now, that should have looked like this (Holliday, 2023). Without internet pitstops, as with the taia777 example, we cannot uncover the tools (Sime, 2023) with which we use to re-activate the present and the future we hope(d) to live.

Time scholars and researchers interested in how digital spaces are sites for people to express feelings of disenfranchisement, alienation, or loss should consider internet pitstops as one of many sites that can tell us how people are coping with the present under postmodernity, but potentially, the groundwork for a grassroots movement to actualise an alternative future. There are potentially other social media platforms such as Reddit for its forums, or ‘subreddits’ (Jamnik and Lane, 2017; Luong and Lomanowska, 2022), or Discord for its community that includes video, textual, and interactive content, to be considered as internet pitstops with its own unique interactions and merits of social time. Nonetheless, and for this essay, YouTube continues to be the most preferred way of accessing and redefining social time. Trump's shooting inspired people to revisit Reagan's to cope with this event, the resurgence of Frutiger Aero signals a desire to escape the nostalgic present (Fisher, 2014), and internet pitstops that form in spite of Nintendo's removal of them are indicative of a shift to ‘reclaim time’, which Sarah Sharma (2022) underscores, is ‘not to catapult into a new novel temporal order. Rather, it is to continue to name the chronometers of social control, [to] reckon with how these chronometers work so well together, and figure out how they can be both struggled against and joyfully averted’ (47). Emerging trends like the term anemoia, or the nostalgia for a time one never lived through, are neo-emotions (Cottingham, 2023) that are as much a linguistic ‘turn’ as they are the expressed desire to turn away from existing and conventional methods of communicating everyday life in the present. Internet pitstops offer not only unconventional ways of communicating time – with timestamps – but also ways of reconstituting time that ‘seeks to exist outside of the dominant temporal order’ (Sharma, 2022: 47). Travellers of internet pitstops retrieve souvenirs and leave postcards (Sime, 2023) that do not necessarily come from the past; they may be creating these artifacts in preparation to visit these lost futures for the first time.

Notes

1. Yet another way at demarcating the status, as well as the time and place for certain social time expressions.

2. I would also like to point out the use of the word ‘pledge’ here, signalling that young people want to, and need to, learn these social time expressions in order to be accepted by their peers.

3. Whilst the video is an excerpt from a documentary on the Secret Service, the title of the video is “Reagan Assassination Attempt”, reinforcing Lefebvre's (2004) argument that media institutions push forward a presence-less present. Users in search for a time map to the present are led to believe that this video is a viable account for how that time was lived and experienced; yet it neglects the context of the shooting.

4. @Ember2168, comment on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N1Jid5uRFo4.

5. @dertyp6849, same video.

6. @xRetroWAVE, same video.

7. @ifadebarbersupply4696, same video.

8. October 14, 2024 – the former has around 1,700 likes and 42 comments; the latter has 788 likes and 9 comments.

9. @suvignanpothuraju8350, comment on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=49BBs7DMLC4&t=3s

10. @briandjordjevic9969, same video.

11. @chowdercat1776, same video.

12. @HellBound-inc, same video.

13. @Alex_TR1713, same video.

14. @cellyyymo, comment on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a2Ni-JZs00Q&t=3172s

15. @chocomilk4991, same video.

16. @RichardTrevithick8437, same video.

17. @HellmikaHM, same video.

18. @thrashdagnarz8103, comment on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EETV2JNBhcc

19. @KingstonMorse, same video.

20. @oakydoke, same video.

21. @galax.spirits, same video.

22. @reqra73, same video.

23. @dianecat9479, same video.

24. @Driptor_Swagpyre, same video.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Associate Editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their thorough and insightful feedback.

References

Adam B (1995) Timewatch: The Social Analysis of Time. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Adavelli M (2023) How many videos are uploaded on YouTube every day? Available at: https://techjury.net/video/how-many-videos-are-uploaded-to-youtube-a-day (accessed 20 October 2024).

Areni CS, Todres M (2023) How long ago were the ‘good old days’? Comparing the prevalence of nostalgia in YouTube comments on music videos from recent versus distant decades. Applied Cognitive Psychology 37(6): 1455–1462. Crossref.

Ballam-Cross P (2021) Reconstructed nostalgia: Aesthetic commonalities and self-soothing in chillwave, synthwave, and vaporwave. Journal of Popular Music Studies 33(1): 70–93. Crossref.

Birth K (2017) Time Blind: Problems in Perceiving Other Temporalities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Crossref.

Boym S (2001) The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books.

Braudel F (1980) On History, (Trans. S. Matthews). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brown MG, Carah N, Tan XY, et al. (2024) Finding the future in digitally mediated ruin: #nostalgiacores and the algorithmic culture of digital platforms. Convergence 30(5): 1710–1731. Crossref. Web of Science.

Bruer J, Kohne J, Mohseni MR (2023) Using YouTube data for social science research. In: Skopek J (ed) Research Handbook on Digital Sociology. Cheltenham, UL: Edwar Elgar Publishing, pp.258–277. Crossref.

Campbell K (2024) The internet phenomenon ‘brain rot’ has taken over the minds of impressionable children and promotes a world of consumerism, obsession, and mental illness. Available at: https://thecentraltrend.com/150355 (accessed 25 October 2024).

CBC Kids News (2024) What is brain rot? Teens explain what it’s weird and fun. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PfaxXqiCSiQ (accessed 23 April 2025).

CNBC Television (2024) Donald Trump Junior speaks at the republican national convention. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZIk62bNWgtg&t=902s (accessed 29 October 2024).

Cole R (2020) Vaporwave aesthetics: Internet nostalgia and the utopian impulse. ASAP Journal 5(2): 297–326.

Cook S (2024) A comprehensive analysis of YouTube statistics in 2024. Available at: https://www.comparitech.com/tv-streaming/youtube-statistics (accessed 2 October 2024).

Cottingham MD (2023) Neo-emotions: An interdisciplinary research agenda. Emotion Review 16(1): 5–15. Crossref. Web of Science.

Dovydaitis G (2021) Celebration of the hyperreal nostalgia: Categorization and analysis of visual vaporwave artefacts. Art History & Criticism 17(1): 113–134. Crossref.

Fisher M (2014) Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Winchester, UK: Zero Books.

Friberg A (2022) On the need for (con)temporary utopias: Temporal reflections on the climate rhetoric of environmental youth movements. Time & Society 31(1): 48–68. Crossref. Web of Science.

Frutiger Aero (n.d.) Frutiger aero aesthetics. Available at: https://frutiger-aero.org/frutiger-aero (accessed 3 November 2024).

Haan K, Watts R (2024) Top website statistics for 2024. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/software/website-statistics/ (accessed 2 October 2024).

Heydari A, Zhang J, Appel S, et al. (2019) YouTube chatter: Understanding online comments discourse on misinformative and political YouTube videos. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.00435.

Holliday L (2023) What is frutiger aero, the aesthetic taking over from Y2K? Available at: https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/58103/1/what-is-frutiger-aero-aesthetic-tiktok-msn-messenger-windows-vista-noughties (accessed 3 November 2024).

Jacobsen MH (2021) Resuscitating the past: Zygmunt Bauman’s critical analysis of the recent rise of retrotopia. In: McKenzie J, Patulny R (eds) Dystopian Emotions: Emotional Landscapes and Dark Futures. Bristol: Bristol University Press, pp.139–158. Crossref.

Jamnik MR, Lane DJ (2017) The use of Reddit as an inexpensive source for high-quality data. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 22(1): 5.

Lefebvre H (2004) Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time, and Everyday Life. London: Continuum.

Luong R, Lomanowska AM (2022) Evaluating reddit as a crowdsourcing platform for psychology research projects. Teaching of Psychology 49(4): 329–337. Crossref. Web of Science.

Mead GH (1934) Mind, Self, and Society From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moreno J (2022) Nintendo once again sent 500+ copyright blocks to remove soundtrack music on YouTube. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johanmoreno/2022/05/31/nintendo-once-again-sent-500-copyright-blocks-to-remove-soundtrack-music-on-youtube (accessed 11 November 2024).

Morris BG (2023) Breaking down the stereotype: Colored people’s time or CP time. In: Newsone. Available at: https://newsone.com/4573705/breaking-down-the-stereotype-colored-peoples-time-or-cp-time/

Niemeyer K (2016) Digital nostalgia. Media Development 4: 27–30.

Oxijinn (2023) とげとげタルめいろスーパードンキーコング2" Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EETV2JNBhcc (accessed 29 October 2024).

Sharma S (2022) Undisciplined time studies. Time & Society 31(1): 44–47. Crossref. Web of Science.

Siersdorfer S, Chelaru S, Nejdi W, et al. (2010) How useful are your comments? Analyzing and predicting YouTube comments and comment ratings. In: 19th international conference on World wide web, New York, USA, 26-30 April 2010, pp. 891–900.

Sime J (2023) Materializing nostalgia: Feet, YouTube, and the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Material Religion 19(1): 34–54. Crossref.

skeuoss (2024) Frutiger aero music playlist mix 7 h of nostalgia, comfort & happiness work, study, chill. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a2Ni-JZs00Q&t=3175s (accessed 1 November 2024).

Sorokin PA, Merton RK (1937) Social time: A methodological and functional analysis. American Journal of Sociology 42(5): 615–629. Crossref.

Tabboni S (2001) The idea of social time in Norbert Elias. Time & Society 10(1): 5–27. Crossref. Web of Science.

Thelwall M (2017) Social media analytics for YouTube comments: Potential and limitations. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21(3): 303–316. Crossref.

Thurnell-Read T (2022) A couple of these videos is all you really needed to get pumped to skate: Subcultural media, nostalgia and re-viewing 1990s skate media on YouTube. YOUNG 30(2): 165–182. Crossref. Web of Science.

Tiffany K (2025) The case for brain rot. The Atlantic, 13 January. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2025/01/brain-rot-language/681297/

Washington Post (2024) Trump previews ‘golden age’ for America in victory speech. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aQbZIPO6t_4 (accessed 8 November 2024).

Weekman K (2024) What is ‘brain rot’? TikTokers are using the term to describe the impact of being ‘chronically online.’ In: Yahoo! News. Available at: https://www.yahoo.com/news/what-is-brain-rot-tiktokers-are-using-the-term-to-describe-the-impact-of-being-chronically-online-211105483.html

Wikitubia (2024) taia777. Available at: https://youtube.fandom.com/wiki/Taia777 (accessed 30 October 2024).

Wilson J (1999) ‘Remember when…’: A consideration on the concept of nostalgia. ETC: A Review of General Semantics 56(3): 296–304.

Wilson J (2014) Nostalgia: Sanctuary of Meaning. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing.

Yazgan AM (2025) The problem of the century: Brain rot. OPUS – Journal of Society Research 22(2): 211–221.

Yousef AMF, Alshamy A, Tlili A, et al. (2025) Demystifying the new dilemma of brain rot in the digital era: A review. Brain Science 15(3): 83. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

YouTube Culture & Trends (2020) Watching the pandemic: What YouTube trends reveal about human needs during covid-19. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/trends/articles/covid-impact/ (accessed 27 October 2024).

Zerubavel E (2003) Time Maps: Collective Memory and the Social Shape of the Past. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Crossref.